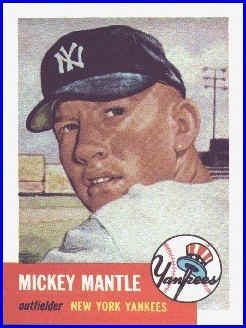

7 - Mickey Mantle

This page includes great photos, stats, history, quotes, speeches, articles, and much more...

note: Mickey Mantle is my favorite player of all-time and therefore you will see many more photos of him than anyone else on this site. Thanks.

Born: October 20, 1931 in Spavinaw, OK.

Died: August 14, 1995 in Dallas, TX.

Height: 6-0, Weight: 201.

Threw right and switch hit.

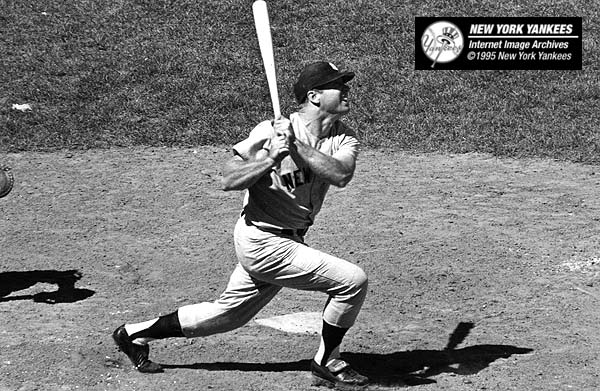

Number retired in 1969. The Mick was the most feared hitter on the most

successful team in history. In his best seasons, and there were many, Mantle was

simply a devastating player. He could run like the wind and hit tape measure

homers, like his famous 565-footer in Washington in 1953. He led the Yanks to 12

fall classics in 14 years, and seven World Championships. He still owns records

for most homers, RBI, runs, walks, and strikeouts in World Series play. In 1956,

Mantle had one of the greatest seasons ever at the plate. He hit 52 homers with

130 RBI and a .353 average to win the Triple Crown. Mantle was elected to the

Hall of Fame in 1974.

With the twentieth century nervously ticking to a close, it is time for retrospectives. The New York Yankees have more to look back on than most: the most successful franchise in the history of team sports, composed of the greatest players in the history of baseball. To honor those players and the century they conquered and made their own, Yankees.com presents the New York Yankees All-Century Team.

|

MICKEY MANTLE: 1951-1968 |

||||||

|

KEY YANKEES NUMBERS |

||||||

|

G |

AVG |

SLG |

OBP |

R |

HR |

RBI |

|

2401 |

.298 |

.557 |

.423 |

1677 |

536 |

1733 |

|

PEAK YANKEES SEASON - 1956 |

||||||||||||||

|

G |

AB |

R |

H |

2B |

3B |

HR |

RBI |

BB |

K |

SB |

CS |

AVG |

SLG |

OBP |

|

150 |

533 |

132 |

188 |

22 |

5 |

52 |

130 |

112 |

99 |

10 |

1 |

.353 |

.705 |

.467 |

American League MVP- 1956, 1957, 1962

Led AL in Home Runs- 1955, 1956, 1958, 1960

Career Grand Slams- 9

Pinch Hit Home Runs- 7

Three Home Runs in One Game- May 13, 1955

AL All Star Game- 1952-1965 (selected to both games 1959-1962)

Gold glove Award- 1962

Elected to Baseball Hall of Fame - 1974

AL All-Star Game: 1952-1965; selected to both games, 1959-1962

AL MVP: 1956, 1957, 1962

Career grand slams: 9

Career home runs: 536 (eighth place)

Elected to Baseball Hall of Fame: 1974

Gold Glove: 1962

Led AL in home runs: 1955-56, 1958, 1960

Most at-bats for the Yankees: 8,102

Most games played for the Yankees: 2,401

Won AL Triple Crown: 1956

Regular season Year Team G AB R H 2B 3B HR RBI Avg. 1951 New York (A) 96 341 61 91 11 5 13 65 .267 1952 New York (A) 142 549 94 171 37 7 23 87 .311 1953 New York (A) 127 461 105 136 24 3 21 92 .295 1954 New York (A) 146 543 129 163 17 12 27 102 .300 1955 New York (A) 147 517 121 158 25 11 37 99 .306 1956 New York (A) 150 533 132 188 22 5 52 130 .353 1957 New York (A) 144 474 121 173 28 6 34 94 .365 1958 New York (A) 150 519 127 158 21 1 42 97 .304 1959 New York (A) 144 541 104 154 23 4 31 75 .285 1960 New York (A) 153 527 119 145 17 6 40 94 .275 1961 New York (A) 153 514 132 163 16 6 54 128 .317 1962 New York (A) 123 377 96 121 15 1 30 89 .321 1963 New York (A) 65 172 40 54 8 0 15 35 .314 1964 New York (A) 143 465 92 141 25 2 35 111 .303 1965 New York (A) 122 361 44 92 12 1 19 46 .255 1966 New York (A) 108 333 40 96 12 1 23 56 .288 1967 New York (A) 144 440 63 108 17 0 22 55 .245 1968 New York (A) 144 435 57 103 14 1 18 54 .237 Totals 2401 8102 1677 2415 344 72 536 1509 .298

World Series Year Opponent G AB R H 2B 3B HR RBI Avg. 1951 New York (N) 2 5 1 1 0 0 0 0 .200 1952 Brooklyn 7 29 5 10 1 1 2 3 .345 1953 Brooklyn 6 24 3 5 0 0 2 7 .208 1955 Brooklyn 3 10 1 2 0 0 1 1 .200 1956 Brooklyn 7 24 6 6 1 0 3 4 .250 1957 Milwaukee 6 19 3 5 0 0 1 2 .263 1958 Milwaukee 7 24 4 6 0 1 2 3 .250 1960 Pittsburgh 7 25 8 10 1 0 3 11 .400 1961 Cincinnati 2 6 0 1 0 0 0 0 .167 1962 San Francisco 7 25 2 3 1 0 0 0 .120 1963 Los Angeles 4 15 1 2 0 0 1 1 .133 1964 St. Louis 7 24 8 8 2 0 3 8 .333 Totals 65 230 42 59 6 2 18 40 .257

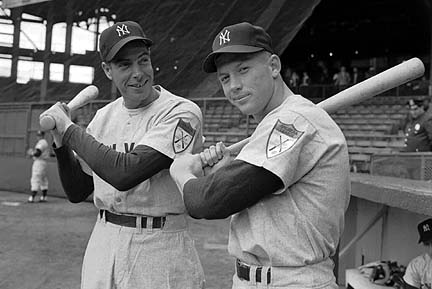

With all due respect to Earle Combs and Bernie Williams, the title of greatest centerfielder in the history of the New York Yankees comes down to Joe DiMaggio and Mickey Mantle, with Mantle rating the edge.

With both players, there are so many "what ifs" that it's easy to lose track of how good they were. What if DiMaggio's career was not interrupted by World War II? What if left field at Yankee Stadium wasn't so bloody deep? What if he hadn't gotten hurt so often? What if Mantle hadn't torn up his knee in the 1951 World Series? What more could he have accomplished if not for the osteomyelitis, the torn hamstring, the broken foot, the infinity of other injuries?

Would he have hit more home runs than Roger Maris if not for the virus and the abscessed hip that shut him down in September, 1961? What if Mantle had not been obsessed by the early deaths of male members of his family and had taken better care of himself? The careers of both men ended decades ago, but the questions are forever. Their accomplishments having long since been set in stone, it's easy to forget about them and focus on what could have been.

So what is left after all of the unfulfilled promise? Lots. DiMaggio was the ultimate precision ballplayer, consistent, conscious of never giving less than his best lest the fans think that he was easing up. Rarely striking out, DiMaggio lashed doubles, triples, and - despite Yankee Stadium - home runs. Fast, he did not steal many bases due to the conservative era in which he played, but he was a fantastic base runner and a graceful outfielder.

Mantle was less disciplined than DiMaggio, but his results were even better. The greatest switch-hitter of all time, Mantle twice popped over 50 home runs, recorded averages as high as .365, and drew about 120 walks a year. In this, he exceeded DiMaggio: though DiMaggio out-hit Mantle .325-.298, Mantle reached base more often, .421-.398. Mantle's patience made him a run-scoring machine.

Mantle scored over 100 runs in nine seasons and was over 90 in three more. Despite his many leg injuries, Mantle was also lightning-fast, clocked going from home to first in 3.1 seconds. He was an excellent percentage base-stealer, could drag bunt for a hit, and almost never hit into a double play. His speed also showed itself in his outfield play, as did his strong arm.

Both players earned three Most Valuable Player awards and played on the winningest teams of their eras. Each was, in his own way, a team leader, and played well under pressure, as DiMaggio demonstrated with his hitting streak and the way he personally destroyed the Red Sox in 1949, and Mantle showed with his record 18 World Series home runs.

The chief factor that separates Mantle from DiMaggio is offensive context. DiMaggio's leagues of the 1930s and early 1940s were far more permissive offensively than Mantle's 1950s, and bear no comparison at all to the 1960s, an era where pitching gradually became more and more dominant. Had Mantle played from 1936 to 1941, his numbers very well may have been even better. Mantle's raw power and patience made him a more productive hitter than DiMaggio; in the same time and place that distinction would have been distinctly apparent. DiMaggio was not always the most productive hitter of his time; there was no one close to Mantle for most of his career.

Another factor is durability. Although Mantle was frequently hurt, he was generally able to play through his injuries. Mantle taping his legs before every game is one of the most famous and dramatic images in the history of the Yankees. Due to the nature of his injuries (and perhaps his fear of being seen at less than his best) DiMaggio was far less likely to play hurt. He also lost time to hold-outs. As such, Mantle played in a higher percentage of team games than DiMaggio did.

There is speed and athleticism. DiMaggio was quick. Mantle was fast. DiMaggio was a consummate base runner, but Mantle could fly. It was this quality that allowed Mantle to be productive past his peak, whereas DiMaggio had to quit.

The World Series record also argues in favor of Mantle over DiMaggio. DiMaggio played 51 games against tough October pitching, hitting .271 with 8 homers in 199 at bats. Mantle hit only .255, but slugged .535 and collected his usual number of walks, making him the most productive hitter in the history of the Series.

It's hard to choose between two of the greatest centerfielders of all time (maybe we could shift the Yankees' greatest left fielder of all time to DH), but the choice comes down to this: Mantle was not only one of the greatest players in the history of the Yankees, he was also the best athlete. That combination is impossible to beat.

BY STEVE WULF

Leonardo da Vinci stood on one end of the stage, Mickey Mantle on the other. The Mick seemed a little out of place in the company of Da Vinci, Abraham Lincoln, Frederick Douglass, Laura Ingalls Wilder and Mahatma Gandhi, but this was my son's third-grade class biography project, titled Who Am I?, and an understanding teacher had allowed him to portray his favorite baseball player, a preference passed down like dna from both his mother and his father. "I was born in Spavinaw, Oklahoma, in 1931," said this child born in New York City in 1986, "and my father named me after his favorite player, Mickey Cochrane. I grew up in Commerce, Oklahoma, and later became known as the Commerce Comet ... Who am I? Hi, I'm Mickey Charles Mantle."

Who was Mickey Mantle? According to the facts provided by my son, the switch-hitting centerfielder played in 2,401 games for the New York Yankees from 1951 until 1968, won the Most Valuable Player award three times, hit a record 18 homers in 12 World Series and entered the Hall of Fame in 1974. Although he was known as No. 7--my son turned his back to the audience to show off the number on the back of the uniform his mother had made for him--he wore No. 6 when he first came up to the Yankees as a 19-year-old rookie. In 1953 he slugged the longest home runs ever measured, 565 ft., off Chuck Stobbs of the Washington Senators, and in 1956 he won the rare Triple Crown (.353 batting average, 52 homers, 130 runs batted in). He accomplished all this even though he played in pain all the time.

Left out of the third-grade presentation were Mantle's depression over the death of his father, at only 39, from Hodgkin's disease; his constant and fatalistic drinking; his bumpkinish trust in swindlers; and the indifferent treatment he gave his wife and four sons, one of whom, Billy, died last year at the age of 36, having suffered from Hodgkin's disease. In his later years, Mantle tried to atone for his sins, entering the Betty Ford Center, freely admitting his alcoholism and making peace with his sons. Mickey Jr., David and Danny were by his side when Mantle died of a rapidly spreading hepatoma at Baylor University Medical Center early Sunday morning.

Who was Mickey Mantle, or more precisely, what was it about him that inspired the fierce devotion of four generations of fans? He was handsome, of course, in the way high school heroes were thought to be. There was music in that name; even he said it sounded "made up." He was a country boy in the big city. He came along at a time when the TV set became the centerpiece of the living room. He was Superman in pinstripes. The eternal debate as to who was the best centerfielder in New York City, Mantle, Willie Mays of the Giants or Duke Snider of the Dodgers, was really no contest, even though Mantle personally deferred to Mays. According to Roger Angell, the peerless baseball writer for The New Yorker, "You watched Willie play, and you laughed all the time because he made it look fun. With Mantle, you didn't laugh. You gasped."

There was something more to Mantle, something all of us picked up from his most ardent admirers--his teammates. They would watch him come into the clubhouse (sometimes after a late night drinking), tape his legs from buttocks to ankle, then go out and hit tape-measure homers. Unlike the aloof Joe DiMaggio, whom he replaced at center, Mantle was generous and funny and self-effacing. Even in 1961, when he and Roger Maris were chasing Babe Ruth's home-run record, Mantle was supportive of Maris. "I'll always be a Yankee," he once said, and indeed, he followed the fortunes of the club religiously.

Though Mantle had been sober for more than a year, 42 years of drinking caught up to him on May 28, when he entered Baylor Medical complaining of stomach pains. On June 8 he received a liver transplant that outraged those who thought, incorrectly, that he got preferential treatment.

Over the years, Mantle may have lost several fortunes, but he never lost his sense of humor. At a press conference a month after the transplant, Mantle spotted noted collector Barry Halper and asked, "Barry, what did you pay for my old liver?" The prognosis for Mantle was hopeful then. But an undetected lung cancer began to spread, and on Aug. 4 he re-entered the hospital.

Last Thursday some of his old teammates gathered at his bedside: Whitey Ford, Hank Bauer, Moose Skowron, Bobby Richardson, Johnny Blanchard. "He's got a tough battle," said Richardson. "But every time he talks there's a laugh in his voice." Mantle was said to be especially appreciative of an autographed "Get Well, Mick" ball from the 1995 Yankees.

Imagine. Baseball's most cherished autographer touched by a ball signed by the current Yanks. But then, that was Mickey Mantle.

Mickey Mantle, 63, the superstar slugging center fielder of the New York Yankees of the 1950s and 1960s whose baseball feats and golden good looks made him an American legend, died of liver cancer yesterday at Baylor University Medical Center in Dallas.

His life in baseball and afterward was the pith and marrow of a basic American myth, and it reflected high triumph and tragedy. Mantle was the clean-cut country boy from Commerce, Okla. The "Commerce Comet" joined the Yankees at age 19, overcoming adversity early on and taking the big city by storm.

With a telegenic, boyish grin, an aw-shucks Oklahoma drawl and a big No. 7 across his muscular back, he became everyone's idea of what a great baseball player should look and sound like. His Homeric feats on the field and love of play off it endeared him to America. He became bigger than the sport itself.

After he retired, his celebrity status continued, and he drew large crowds to autograph shows and his baseball camps and appeared on TV talk shows and even music videos. But as a Yankees superstar, he had developed a taste for high living and good liquor that only accelerated after his playing days ended, and he eventually became a chronic alcoholic. He was treated for alcoholism, and his damaged liver eventually was ravaged by cirrhosis, hepatitis C and the cancer that led to his death.

Mantle played for the Yankees from 1951 through 1968 and was a vital element in a Yankees tradition and mystique that transcended the boundaries of sports. To millions, the Yankees stood for winning, invincibility and being the best, and Mantle, as the successor to the likes of Joe DiMaggio, Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig, was a major force in preserving and enhancing that image.

He played alongside such other legends as outfielder Roger Maris, catcher Yogi Berra and pitcher Whitey Ford. Not only were they teammates but they also were friends off the field. And from the time Mantle joined the Yankees through 1960, his manager was the colorful and eccentric Casey Stengel. Mantle was one of a trio of 1950s New York center fielders immortalized in legend and in the 1980s hit song "Willie, Mickey and the Duke," along with the New York Giants' Willie Mays and the Brooklyn Dodgers' Duke Snider.

For most of Mantle's career, the Yankees dominated major league baseball, and he was considered by many the greatest player on baseball's greatest team. Mantle helped lead the Bronx Bombers to 12 American League pennants and seven World Series titles. His 18 home runs in World Series play still stands as a record.

Mantle was voted the American League's most valuable player three times -- in 1956, 1957 and 1962 -- and finished his career with 536 regular season home runs. When he retired, he was third on the all-time home run list, behind Babe Ruth and Willie Mays, and almost 30 years later, he is still eighth all-time. He hit more than .300 five straight years and hit a career high of .365 in 1957. He ended his career with 1,509 runs batted in. Ten times, he homered from both sides of the plate in the same game.

Injuries plagued Mantle throughout his career. He played more games for the Yankees -- 2,401 -- than anyone else, and for much of that time he played in pain. In the second game of the 1951 World Series, he injured his knee while chasing a fly ball when a cleat on his shoe caught on a piece of the underground lawn sprinkler apparatus in the outfield at Yankee Stadium. He missed the rest of the series and later underwent the first of several knee operations.

Despite his injuries, for several years he was the fastest man on the team and one of the fastest in the American League. As an outfielder, he could outrun a fly ball. When Don Larsen pitched a perfect game against the Dodgers in the 1956 World Series, he got a major assist from Mantle. A line drive by Dodgers first baseman Gil Hodges appeared certain to fall safely in left-center field until a speeding Mantle caught up with it, snaring the ball with a backhand catch.

Mantle was one of the most powerful hitters in baseball, but he also was a good bunter and a brilliant base runner. As a young man, he was timed at 2.9 seconds reaching first base on a bunt. He was a switch hitter, and his swing was described as ferocious. In 1953, against the Washington Senators, he hit a ball 565 feet into the street beyond the left-center-field bleachers at Griffith Stadium. He also struck out often, 1,710 times during his major league career.

"When you keep aiming for the fences, you're bound to strike out a lot . . . ," Mantle said in his 1985 autobiography, "The Mick." "Stan Musial and Ted Williams were both every bit as strong as I am. The difference is that they were always trying to meet the ball, while I always wanted to kill it. If you swing for distance, you almost have to have the bat in motion before the pitch is even released."

He retired with a lifetime batting average of .298, which was a disappointment to many of Mantle's fans and to Mantle himself. Years later, he told friends that he wished he'd retired after the 1964 season, his last year of greatness, when he batted .303 and hit 35 home runs. Had he left the game after that season, Mantle's career batting average would have been well over .300. But his last four years were not good ones. His legs hurt. His knees hurt. And his batting average sank.

In February 1969, Mantle reported for spring training with the Yankees intending to play for one more season. But on March 1, he announced his retirement. "I can't play anymore," he said. "I don't hit the ball when I need to. I can't steal when I need to. I can't score from second when I need to. . . . I never wanted to embarrass myself on the field or hurt the club in any way or give the fans anything less than what they are entitled to expect from me."

Five years later, in 1974, he was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Mickey Charles Mantle was born Oct. 20, 1931, in Spavinaw, Okla. He was named for Mickey Cochrane, the great hitting catcher of the Philadelphia Athletics and the Detroit Tigers. His father, Mutt Mantle, was a lead and zinc miner who had played semiprofessional baseball, and his grandfather Charles Mantle had played baseball on a mining company team.

The two men drilled the boy in the fundamentals of baseball from an early age, and it was at their insistence that he learned to be a switch hitter. By the time young Mickey was a teenager, he was playing baseball 12 to 14 hours a day, day after day. At high school in Commerce, where the family had moved when he was 4, Mantle played on the football, basketball and baseball teams.

During a football practice in 1946, he was kicked in the left shin while carrying the ball, an accident that caused a chronic bone infection called osteomyelitis. At one point, Mantle's doctors thought his leg might have to be amputated, but Mantle's family refused to consider that, and the condition was arrested after several operations. It would cause his draft board to reject him four times as physically unfit for military service.

While still in high school, Mantle also played baseball for a team called the Whiz Kids in a league for players younger than 21. He was noticed by a scout for the Yankees' organization named Tom Greenwade, who signed him to a minor league contract the day he graduated from Commerce High School. He received a $1,150 signing bonus and a salary of $140 a month to play for the Independence, Kan., team in the Class D Kansas-Oklahoma-Missouri League.

Two years later, as a 19-year-old shortstop, he joined the Yankees at spring training, widely publicized and eventually heralded as the replacement for the aging DiMaggio. Stengel, the manager, called him "my phenom." In spring training that year, he hit several monumental home runs, including one against the University of Southern California that was said to have traveled more than 600 feet. That only fueled the already intense media interest.

At shortstop, Mantle was an atrocious fielder, so the Yankees switched him to the outfield, where he began the 1951 season. After slumping badly, he was sent down to the Yankees' farm club at Kansas City, Mo., but he returned to the Yankees near the end of the season and ended with a .297 batting average and 13 home runs in 96 games. He was in the starting lineup for the World Series against the Giants and played until he injured his knee in the second game.

The day after that momentous game, Mantle's father accompanied the young outfielder to the hospital. Mutt Mantle, then in his late thirties, told his son to rest his knee by leaning on him as they entered the hospital. Mantle's father collapsed under the weight, both men crashing to the pavement in pain.

Hospitalized in the same room, the outfielder was treated for torn knee ligaments and the father was diagnosed with Hodgkin's disease, which killed him less than a year later. Mickey Mantle's grandfather and an uncle both had died young of the same ailment, and in his thirties he also would lose a son to Hodgkin's. Mantle admitted that he always feared that he, too, would die young of Hodgkin's.

He once spoke of the pain of losing his father. "I was devastated, and that's when I started drinking," he said. "I guess alcohol helped me escape the pain of losing my dad."

The next year, his first full season as a Yankee, Mantle hit .311 with 23 home runs in 142 games. Four years later, in 1956, he won the first of his three most valuable player awards and also captured the Triple Crown by leading the American League in batting, at .353; in home runs, with 52; and in runs batted in, with 130. He was MVP the next year, also, batting .365.

In 1961, Mantle and Maris battled each other for the home run title, with Maris winning and breaking Ruth's record, with 61. Mantle hit 54 home runs that year, his career best. The 1961 team set a major league record with 240 home runs and included six players who hit 20 or more.

Off the field, he developed a reputation as a late-night carouser, which he later admitted had likely shortened his career. In his dealings with the public, he could be gracious or callous, depending on his moods. Jim Bouton, a pitcher with the Yankees in the early 1960s, described Mantle in his book "Ball Four" as equally capable of shoving autograph-seeking children out of his way or taking time to mingle with, talk to and sign autographs for hundreds of admirers.

In retirement, Mantle participated in managing a variety of businesses, including restaurants and clothing stores. In 1983, baseball's commissioner, Bowie Kuhn, banned him from baseball for doing public relations assignments for an Atlantic City casino. Two years later, Kuhn's successor, Peter Ueberroth, reinstated Mantle. Early in 1994 -- warned by doctors that his next drink might be his last -- Mantle checked himself into the Betty Ford Center in Rancho Mirage, Calif., for a 28-day program of rehabilitation from alcohol abuse. He later wrote about that experience in a cover story for Sports Illustrated magazine. "God gave me a great body to play with, and I didn't take care of it. And I blame a lot of it on alcohol," he declared.

After leaving the Betty Ford Center, Mantle remained sober, but the damage to his body from years of heavy drinking had been done. He developed liver cancer, and a long-dormant hepatitis C infection flared up. On June 8, he underwent a liver transplant, which appeared to have been successful.

Early in August, the cancer from Mantle's diseased liver was detected in his lungs, and he was readmitted to Baylor Medical Center. Doctors soon discovered that it had spread to other parts of his body. Drugs he had taken to prevent his body from rejecting the new liver had weakened his immune system, making it easier for the cancer to spread, doctors said.

At a news conference several weeks before his death, the man idolized by millions for his grace and power expressed remorse for his years of heavy drinking. He declared that he was no role model for America's youth. "Don't be like me," he warned.

Survivors include his wife of 43 years, Merlyn, of Dallas; and three sons, Danny, David and Mickey Jr.

| Mickey Mantle's |

| 1961 World Championship Ring |

|

|

|

|

Quotes from the Mick

1. "I guess you could say I'm what this country

is all about."

Mickey Mantle

2. "All I had was natural ability."

Mickey Mantle

3. "It was all I lived for, to play

baseball."

Mickey Mantle

4, "The only thing I can do is play baseball. I

have to play ball. It's the only thing I know."

Mickey Mantle

5. "I always loved the game, but when my legs

weren't hurting it was a lot easier to love."

Mickey Mantle

6. "I'll play baseball for the Army or fight

for it, whatever they want me to do."

Mickey in 1951 during the controversy of whether he should

be drafted by the Army

7. "He's the best prospect I've ever

seen."

Branch Rickey on Mickey in 1951

8. "I never saw a player who had greater

promise."

Casey Stengel on Mickey

9. "That boy Mantle is a good one."

Ty Cobb

10. "Mantle had more ability than any player I

ever had on that club."

Casey Stengel

11. "You're going to be a great player,

kid."

Jackie Robinson to Mickey Mantle after the 1952 World

Series

12. "He can run, steal bases, throw, hit for

average, and hit with power like I've never

seen. Just don't put him at shortstop."

Minor league manager Harry Craft on Mickey

13. "His fielding leaves you wondering. Then he

steps up to hit and all doubts start to fade."

New York Post writer Arch Murray on Mickey in spring

training 1951

14. "There isn't any more that I can teach

him."

Yankee great Tommy Henrich on Mickey in spring training in

1951

15. "That kid can hit balls over

buildings."

Casey Stengel on Mickey in 1951

16. "If that guy were healthy he'd hit 80 home

runs."

Carl Yastrzemski on Mickey Mantle

17. "I'd give the Yankees a quarter of a

million dollars for him, and bury him in thousand dollar bills as a signing

bonus."

White Sox G. M. Frank Lane on Mickey in 1951

18. "It's what you're worth."

Yankees' G. M. George Weiss to Mickey after offering him a

$17,000 pay cut for the 1958 season - Mickey batted 12 points higher than in

1956 but hadn't won the Batting Title or the Triple Crown like he did in 1956

19. "I'd say Mantle is the greatest player in

either league."

St. Louis Brown's Manager Marty Marion

20. "Let's see - uh, yes. There's one thing he

can't do very well. He can't throw left-handed. When he goes in for that we'll

have the perfect ballplayer"

St. Louis Brown's Manager Marty Marion when asked if

Mickey had a weakness

Import Dates in Mantle's Life

January 16, 1974 (26 Years): Mickey is elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility.March 1, 1969 (31 Years): Mickey announces his retirement from baseball.

June, 1949 (51 Years): Mickey signs with the Class "D" Independence Miners of the Yankees organization on the day he graduates from high school.

June 8, 1969 (31 Years): "Mickey Mantle Day" is held at Yankee Stadium. 70,000 people attend.

August 12, 1974 (26 Years): Mickey is inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame with friend and teammate Whitey Ford.

August 13, 1995 (5 Years): Mickey passes away in Dallas at age 64.

September, 1949 (51 years): Mickey wins his first championship with the Yankees Organization as the Independence Miners capture the K-O-M (Kansas-Oklahoma-Missouri) league title.

October 10, 1964 (36 Years): Mickey crushes the first pitch from Cardinals' relief pitcher Barney Schultz into the third deck at Yankee Stadium for career World Series homer number 16, breaking Babe Ruth's record.

October 14, 1964 (36 Years): Mickey adds to his World Series home run record by smashing number 17 to beat the Cardinals 8-3 in Game 6 in St. Louis.

October 15, 1964 (36 Years): Mickey belts his 18th and final World Series home run to set the all-time World Series home run record.

October 20, 1931 (69 Years): Mickey is born in Spavinaw, Oklahoma, a small town near Commerce in northwestern Oklahoma.

December 23, 1951 (49 Years): Mickey marries his high school sweetheart, Merlyn Johnson.

|

Mickey's Hall of

Fame Induction Speech |

"He had the foresight to realize that someday in baseball that left-handed hitters were going to hit against right-handed pitchers and right-handed hitters were going to hit against left-handed pitchers; and he taught me, he and his father, to switch-hit at a real young age, when I first started to learn how to play ball. And my dad always told me if I could hit both ways when I got ready to go to the major leagues, that I would have a better chance of playing. And believe it or not, the year that I came to the Yankees is when Casey started platooning everybody. So he did realize that that was going to happen someday, and it did. So I was lucky that they taught me how to switch-hit when I was young.

"My dad really is probably the most influential thing that ever happened to me in my life. He loved baseball, I loved it and, like I say, he named me after a baseball player. He worked in the mines, and when he came home at night, why, he would come out and, after we milked the cows, we would go ahead and play ball till dark. I don't know how he kept doing it. "I think the first real baseball uniform and I'm sure it is the most proud I ever was was when I went to Baxter Springs in Kansas and I played on the Baxter Springs Whiz Kids. We had that was the first time I'll never forget the guy, his name was Barney Burnett, gave me a uniform and it had a BW on the cap there and it said Whiz Kids on the back. I really thought I was somethin' when I got that uniform. It was the first one my mom hadn't made for me. It was really somethin'. "There is a man and a woman here that were really nice to me all through the years, Mr. and Mrs. Harold Youngman. I don't know if all of you have ever heard about any of my business endeavors or not, but some of 'em weren't too good. Probably the worst thing I ever did was movin' away from Mr. Youngman. We went and moved to Dallas, Texas, in 1957, but Mr. Youngman built a Holiday Inn in Joplin, Missouri, and called it Mickey Mantle's Holiday Inn. And we were doin' pretty good there, and Mr. Youngman said, 'You know, you're half of this thing, so why don't you do something for it.' So we had real good chicken there and I made up a slogan. Merlyn doesn't want me to tell this, but I'm going to tell it anyway. I made up the slogan for our chicken and I said, 'To get a better piece of chicken, you'd have to be a rooster.' And I don't know if that's what closed up our Holiday Inn or not, but we didn't do too good after that. No, actually, it was really a good deal. "Also, in Baxter Springs, the ballpark is right by the highway, and Tom Greenwade, the Yankee scout, was coming by there one day. He saw this ball game goin' on and I was playing in it and he stopped to watch the game. I'm making this kind of fast; it's gettin' a little hot. And I hit three home runs that day and Greenwade, the Yankee scout, stopped and talked to me. He was actually on his way to Broken Arrow, Oklahoma, to sign another shortstop. I was playing shortstop at that time, and I hit three home runs that day. A couple of them went in the river one right-handed and one left-handed and he stopped and he said, 'You're not out of high school yet, so I really can't talk to you yet, but I'll be back when you get out of high school.' "In 1949, Tom Greenwade came back to Commerce the night that I was supposed to go to my commencement exercises. He asked the principal of the school if I could go play ball. The Whiz Kids had a game that night. He took me. I hit another home run or two that night, so he signed me and I went to Independence, Kansas, Class D League, and started playing for the Yankees. I was very fortunate to play for Harry Craft. He had a great ball club there. We have one man here in the audience today who I played with in the minors, Carl Lombardi. He was on those teams, so he knows we had two of the greatest teams in minor league baseball at that time, or any time probably, and I was very fortunate to have played with those two teams. "I was lucky when I got out. I played at Joplin. The next year, I cam to the Yankees. And I was lucky to play with Whitey Ford, Yogi Berra, Joe DiMaggio, Phil Rizzuto who came up with me and I appreciate it. He's been a great friend all the way through for me. Lots of times I've teased Whitey about how I could have played five more years if it hadn't been for him, but, believe me, when Ralph Houk used to say that I was the leader of the Yankees, he was just kiddin' everybody. Our real leader was Whitey Ford all the time. I'm sure that everybody will tell you that. "Casey Stengel's here in the Hall of Fame already and, outside of my dad, I would say that probably Casey is the man who is most responsible for me standing right here today. The first thing he did was to take me off of shortstop and get me out in the outfield where I wouldn't have to handle so many balls.

"I listened to Mr. Terry make a talk last night just for the Hall of Famers, and he said that he hoped we would come back, and I just hope that Whitey and I can live up to the expectation and what these here guys stand for. I'm sure we're going to try to. I just would before I leave would like to thank everybody for coming up here. It's been a great day for all of us and I appreciate it very much." Mickey Mantle, August 12, 1974 |

Check out a great Mickey Mantle Tribute Page at: